Eternal Lovers, Endless Nights: “Only Lovers Left Alive” (2013/Film)

This article is based on notes made in 2016, 2018, and 2024. Screen grabs via screenmusings.org.

In the late months of 2016, I found myself caught in the gentle but unrelenting rhythm of a wave that seemed to knock me back and forth, neither calming nor unsettling, but leaving me in a melancholic suspension, as though I were a lost sail, stalled in the vastness of an ocean that never knew of my existance.

My attempts at a career in academia had not panned out, the relationships I attempted to foster failed, and the family restaurant, into which we had poured so many dreams, so much sweat and faith, was closing its doors. There was no drama in these endings—just the slow, bittersweet acknowledgment of yet something else slipping quietly into the unreachable past.

I stood on the threshold of something undefined, unable to discern which direction my life would take, and as if I had no control over where it was heading. I could see several versions of myself flashing somewhere far off, like faint distant Viking funeral, each burning and smoking into some unknown expanse. Would I follow one? Would I abandon them all?

It was a strange time.

Even my time in New York City, a city I had once embraced with such fervor, seemed to be coming to its end. Many of my friends were leaving. The energy that had once coursed through its streets, its crowds, and its ceaseless noise now felt distant, like the sound of a party heard faintly through a wall. It was as if the energy of that city had been spilled, like a broken vase, and it could never be repaired to its true beauty again.

These slow gray days unfolded in a large second-floor apartment in Crown Heights, where I lived alone. I inhabited it like a ghost, moving quietly, observing the traces of light and shadow that shifted with the hours.

I had stopped watching television, only reading and sporadically writing. My library was like a collection of friends.

In the afternoons, I would lie on the wooden floor, watching the sunlight crawl across the walls in slow, golden arcs. And as evening descended, the light would fade, leaving only the gray shadows of dusk and the muted murmurs of the city at night.

On October 8, 2016 I wrote:

I was reading Memory in the Flesh. At some point, I fell asleep. I napped for hours. When I woke up again, I lay there staring at the ceiling. The house was a deep settled quite.

The golden hour came fast. The wind rose hard and sharp. The trees bent and twisted, moving like ribbons caught in a storm. Their shadows flickered on the naked walls and ceilings, quick and jagged and alive, like flames from a cold and brutal fire.

I had never seen anything like it. If I’d been a monk I might have thought it was God speaking. It felt like it was directed at me, and it was the truest thing I’ve felt in months.

Got off the floor to film it after a while. It was wild.

But it wasn’t sadness that I was going through – it was a kind of quiet detachment, a melancholy, as if I were observing the world, a world that was changing in a strange and alien way. And like a prisoner of the sail, I could only wait for the waves to carry me where gods and the winds fated me towards, to love, to death, to infinity, wherever. In the end, I would have been fine with all of it.

It was in this fragile, suspended state that I first encountered Only Lovers Left Alive, Jim Jarmusch’s haunting meditation on love, immortality, and time. The film isn’t one that grips you with plot or action; it moves slowly, dreamlike, unfolding in a rhythm that feels almost like breathing. Watching it, I felt as though it understood the stillness I was living in—not just understood, but inhabited it with me.

I wrote in my journal on November 12, 2016 I wrote:

Another late night. Haven’t watched television since the election, everyone in the city is losing their minds, it’s kind of entertaining. I need new books, I’m growing tired of these.

Around 60 in the afternoon. After sunset found myself all the way in Prospect Park, a long brisk walk. Seems like a dull evening for everyone, passed by many bars and restaurants, mostly empty, waiters and bartenders have that desperate look I know too well in their eyes. Thought about stopping into one of those empty dark dive bars, but I have no money.

Stopped at the bodega on Eastern Parkway and Buffallo Ave. They call themselves a “supermarket” but it is no bigger in sq footage then a gas station convenient store in the Midwest. Got beets, cilantro, dill, onions, capers, potatoes and bacon. Wanted to get eggs, but they kind of looked off in that broken packaging under that unflattering yellow light. Late night snack was frying it all up. Brewed chaga and drank a pretty strong cup.

Finally watched Only Lovers Left Alive, which Mark recommended three years ago. This movie is the best I’ve seen in 3 years. First impressions – longing, survival, love, transcendence. I will probably watch it again tomorrow or tonight.

The film follows Adam (Tom Hiddleston) and Eve (Tilda Swinton), two centuries-old vampires whose love has endured lifetimes but now exists across great distances.

Adam lives in a crumbling Victorian house in Detroit, a recluse surrounded by vintage guitars, analog recording equipment, and Tesla-inspired contraptions that power his isolated world. Once a musician of great influence, he now languishes in despair, disgusted with humanity—whom he calls “zombies”—and disillusioned with his own endless existence.

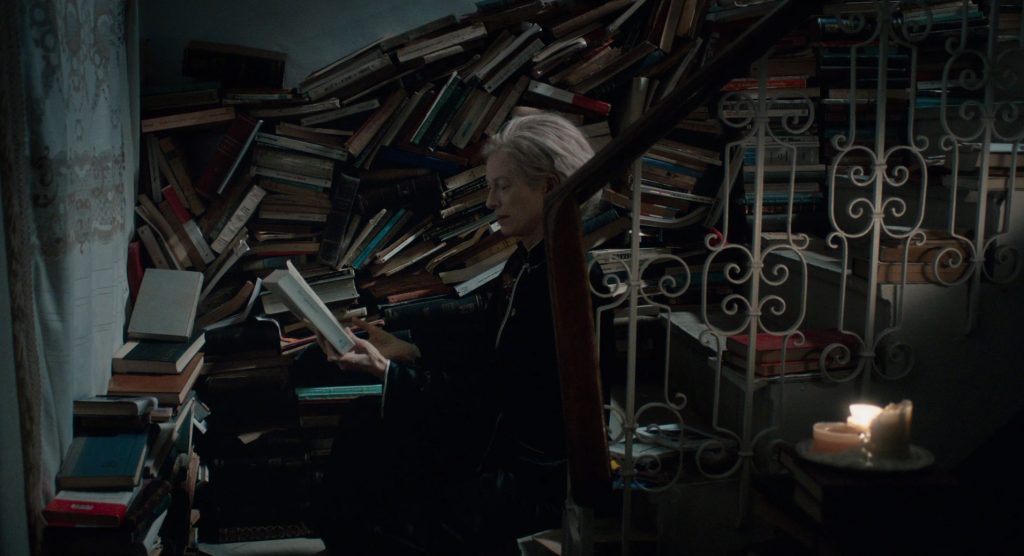

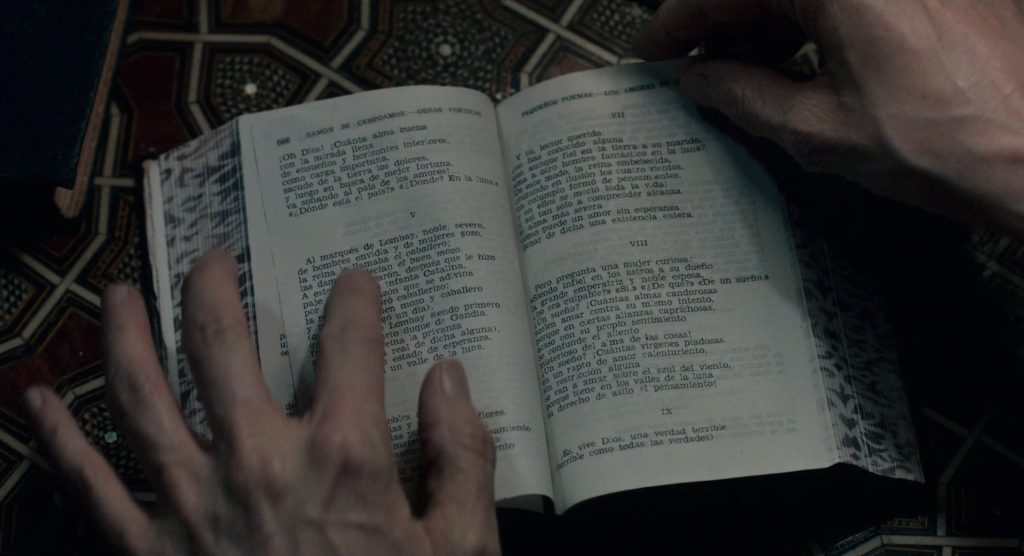

Eve, by contrast, lives in Tangier, surrounded by books she has collected over the centuries. Her evenings are marked by rituals of quiet reverence: reading, wandering the golden-lit streets, and visiting her companion Christopher Marlowe (John Hurt), who Jarmusch imagines as an immortal who faked his death in 1593. Where Adam is mired in the weight of existence, Eve finds beauty in its details.

What struck me first was the film’s pace. It doesn’t rush to explain itself or demand your attention. Instead, it lingers, meditating on textures and moments: the dim light of a Detroit street, the way moonlight falls on an old book, the sound of vinyl spinning on a turntable. Watching it felt like being invited into a world that already existed long before you arrived—a world that would continue with or without you.

There is a scene early in the film where Eve prepares to visit Adam in Detroit. She packs her suitcase, her hands gliding over the spines of books: Kafka, Cervantes, Beckett, Mishima. Each selection feels deliberate, not just a choice but a communion, as though these texts are not merely objects but companions. Watching her, I felt an ache of recognition. I truly appreciated the care and love that the character displays or her books. There is a kindness, a resilience, that they, like her, have survived through the centuries.

Adam’s despair, by contrast, felt almost too familiar. His house, cluttered with relics of a more meaningful past, is both a sanctuary and a prison. Despite the art and music he has contributed to the world, he feels disconnected from it, disillusioned by the mediocrity and corruption of the present. The wooden bullet he commissions for his revolver—a quiet, devastating symbol of his longing for release—haunted me. Watching him, I saw echoes of my own detachment, my own uncertainty about where I was headed and whether any of it mattered.

When Eve arrives in Detroit, her presence offers Adam a brief reprieve. Together, they wander the empty streets, play chess, and listen to music. Their love is not dramatic or fiery; it is steady, enduring, and filled with quiet tenderness. Watching them, I was reminded that even in the most uncertain times, connection—however fleeting—is perhaps what it is all about.

But their peace is short-lived. The arrival of Ava (Mia Wasikowska), Eve’s impulsive younger sister, disrupts their fragile balance. Her recklessness leads to tragedy when she kills Ian (Anton Yelchin), Adam’s human confidant. This moment, like so much in the film, is handled with quiet inevitability. Adam and Eve dispose of Ian’s body and flee to Tangier, carrying only what they can.

The film’s final act lingers in my memory like a half-remembered dream. In Tangier, Adam and Eve visit Marlowe, who succumbs to poisoned blood—a bitter reminder that even immortality cannot shield one from decay. Wandering the streets, desperate and hungry, they hear a haunting melody drifting from a nearby club. The music seems to offer one last gift from a world they have both loved and resented.

In the closing moments, they spot a young human couple embracing. Adam, resigned to their fate, asks, “What choice do we have?” It is a question that lingers beyond the confines of the film—a question about survival, about compromise, about what it means to keep going when everything feels uncertain.

Watching Only Lovers Left Alive, I felt as though it had given me something I didn’t know I needed. It met me in my stillness, in the echoing emptiness of that apartment in Crown Heights, and reminded me that even in solitude, life contains beauty: in books, in music, in fleeting moments of connection. It didn’t offer me answers, but it offered something more enduring—a sense of recognition, a sense that the struggle itself is part of what makes life meaningful.

Years later, the film remains with me. Its quiet wisdom, its haunting mood, its slow, deliberate pace—it feels less like a story and more like a meditation, a reminder that even when we feel untethered, we are still part of something vast and beautiful and meaningful and meaningless all at the same time. If anything, the moment is what matters, for that is when we’re truly ever alive.