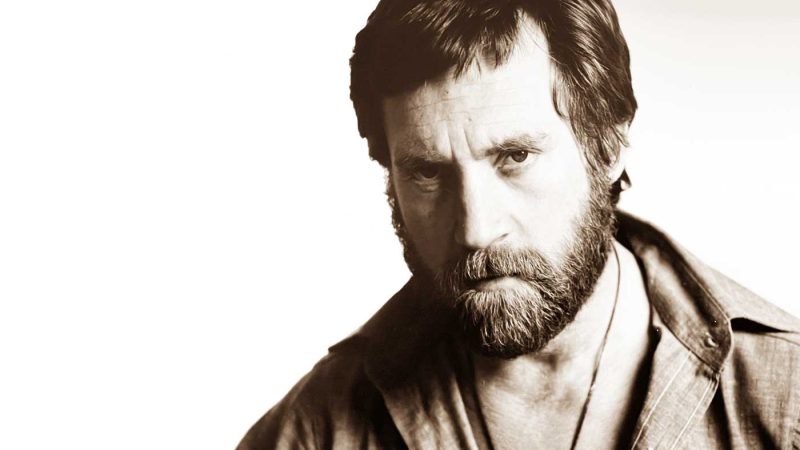

On Vladimir Vysotsky’s 87th Birthday

Every January 25, I ask myself the same question: if Vladimir Vysotsky hadn’t left us in 1980 at just 42, what would he be like today? How would he have adapted to the late ‘80s, the fall of the Soviet Union, and the strange post-Soviet world that followed? Would his sharp baritone and unmatched charisma still keep him a rock star today? I also think about Bulat Okudzhava’s heartbreaking, though beautifully composed and later performed, tribute to Vysotsky in the song About Vladimir Vysotsky. The lyrics capture the grief of losing him so early:

“I decided to compose a song about Volodya Vysotsky:

Another one who won’t return home from his journey.

They say he sinned, that he snuffed out his candle too soon…

He lived as he could, and nature knows no sinless souls.

Parting is brief, just a moment, and then

We’ll set off too, following his still-fiery tracks.

Let his hoarse baritone circle above Moscow,

And we’ll laugh with him, and we’ll cry with him too.”

(Translation by Alexander Pogrebinsky)

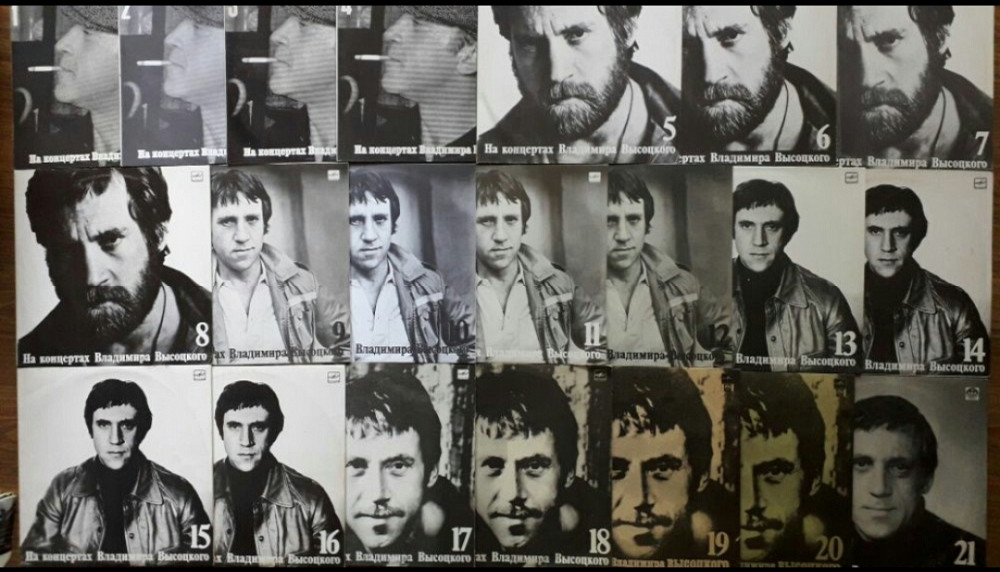

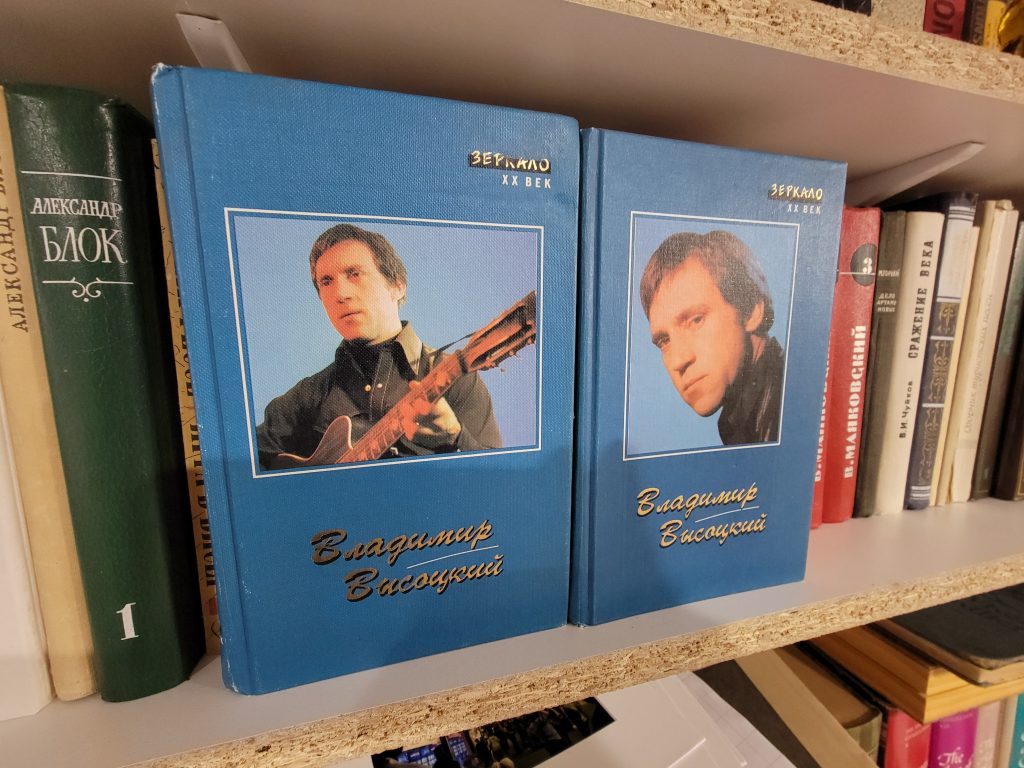

Born in the 1980s in the Soviet Union, I can’t remember a time when Vysotsky didn’t have a hold on my imagination. My parents had a collection of his albums in our home: simple, black-and-white records, with covers that featured striking images of Vysotsky—some from his youth, others from his later years, including the famous shot of him with his cap and cigarette. These records, a collection of over 20 records, titled At The Concerts of Vladimir Vysotsky, recorded during live performances all over the Soviet Union, were my first real connection to him.

In our apartment at the House of Artists in downtown Kiev, I would retreat to my late grandmother’s room to play those albums over and over again. The room is still clear in my memory: the Soviet furniture, the scratchy black-and-white pled blanket on the bed.

I’d lie there for hours, listening to Vysotsky’s war songs from the 1960s and ‘70s. One song, about a dying soldier in a burning tank, especially stayed with me. I’d listen and imagine myself as that soldier, transported by the raw emotion in his voice. These songs became a part of me—they shaped the way I see the world, the way I understand history, poetry, and music.

Those records are still with me today. They’re one of the few things my family was able to bring to the United States when we immigrated, and they’re among my most treasured possessions. Even now, I turn to them when I need to reconnect with my past and to sense that feelings that I had as a child.

Vysotsky is just as important to me as he is to millions of other Soviet and post-Soviet people.

It’s hard to explain who he was in simple terms. Yes, he was a Russian poet and musician, but his work transcended national boundaries. His songs, though written in Russian, became something much bigger during the cultural thaw of the ‘60s and ‘70s. In those years, the cultures of the Soviet republics—Russian, Ukrainian, Kazakh, Belarusian—were intertwined. Vysotsky’s bard songs entered the collective consciousness and became narodnye pesni (folk songs) of a new kind, free from political undertones.

Even now, many people sing these songs without knowing Vysotsky wrote them.

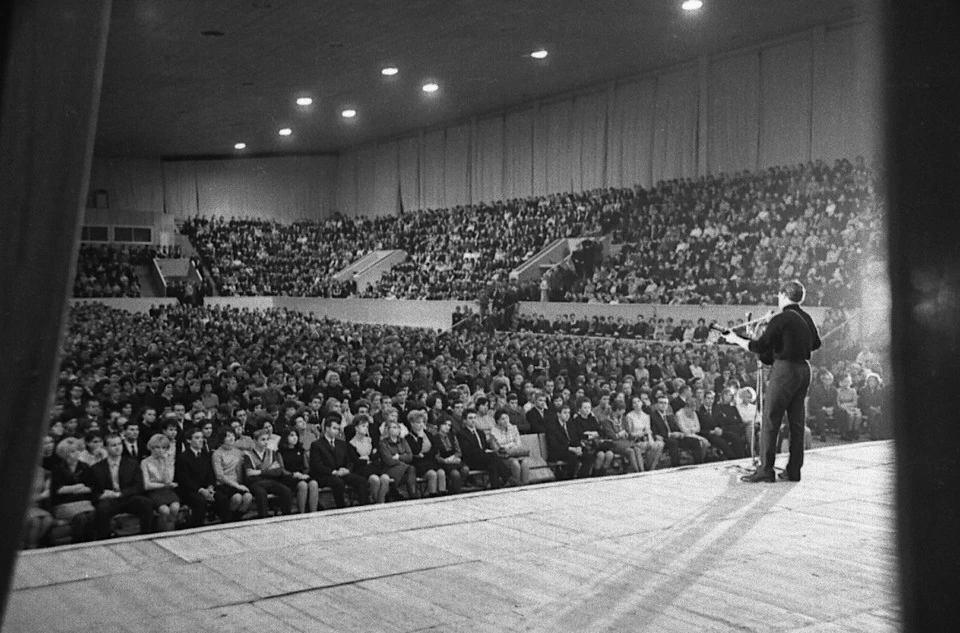

During his lifetime, he drew massive crowds everywhere he went—Kiev, Tashkent, Lviv, Essentuki, you name it. Even in the United States, his tours drew thousands of Russian speakers, as well as people who didn’t understand a word of Russian but were still captivated by him.

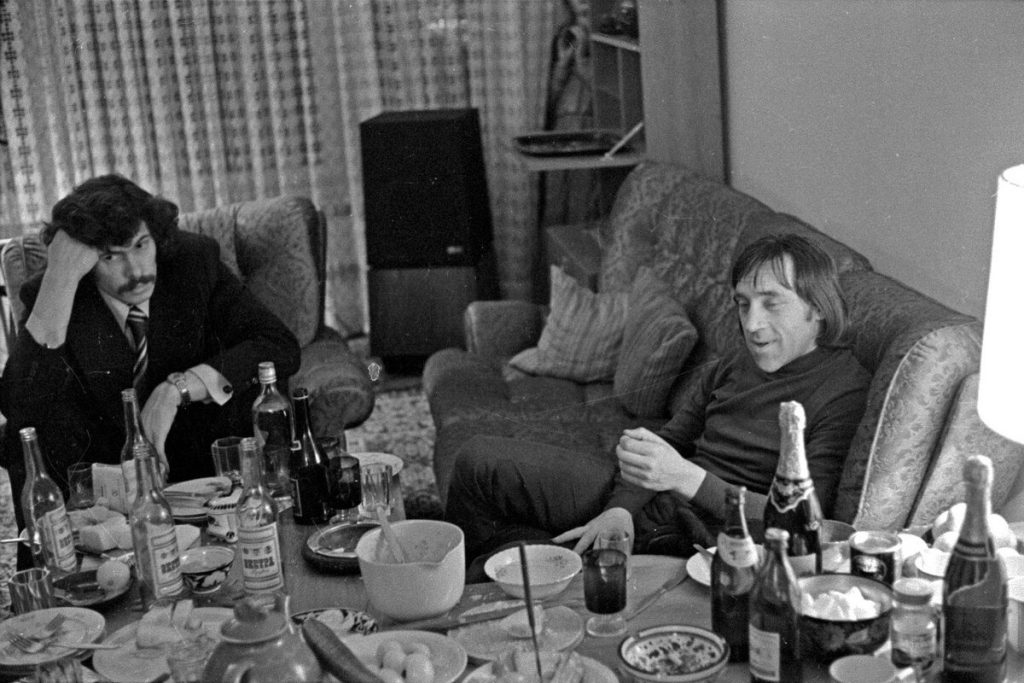

Marina Vlady, his third wife, recalls a party in the 1970s at Warren Beatty’s house where Vysotsky performed. She described how Robert De Niro was completely mesmerized by him, despite the language barrier.

Musically, Vysotsky covered so much ground: blatnye pesni (gritty, street ballads), humor, songs written for films, war ballads, and heartfelt lyrical songs. His range was extraordinary, from rough and dark to light and tender. His songs, especially those written for the film Vertical, and his war songs stand out as some of his most powerful work. That range—his ability to shift between humor and tragedy, toughness and vulnerability—is what made millions love him, and it’s why his music still resonates.

Vysotsky’s life, like his art, was intense. Born on January 25, 1938, in Moscow, he lived through the upheaval of wartime Russia. His father, a WWII colonel, and his mother, a translator, divorced in 1947. He spent part of his childhood in Germany with his mother and stepfather before returning to Moscow, where he discovered music, theater, and poetry. After dropping out of the Moscow Engineering and Construction Institute, he enrolled at the Moscow Art Theatre (MXAT) and began acting. It was there that his love of poetry and music took off.

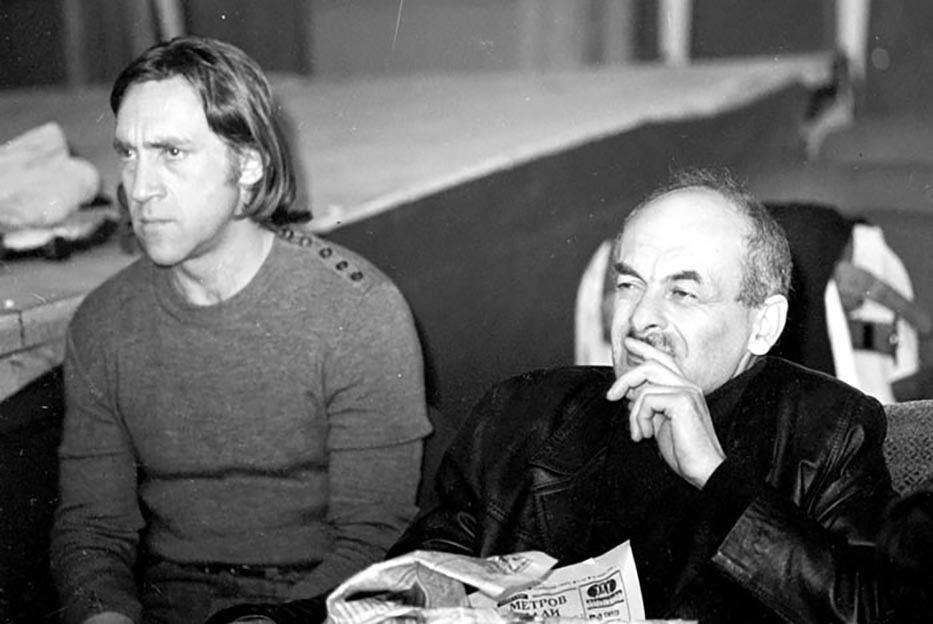

Vysotsky eventually joined the Taganka Theatre, where he found the creative freedom to shine. His acting was magnetic, but it was his songs—raw, emotional, and full of biting commentary—that made him a legend. His breakthrough came with the 1968 film Vertical, for which he wrote the soundtrack, including the iconic “Song About a Friend.” This marked the start of his rise as both a musician and a voice for those who felt unheard.

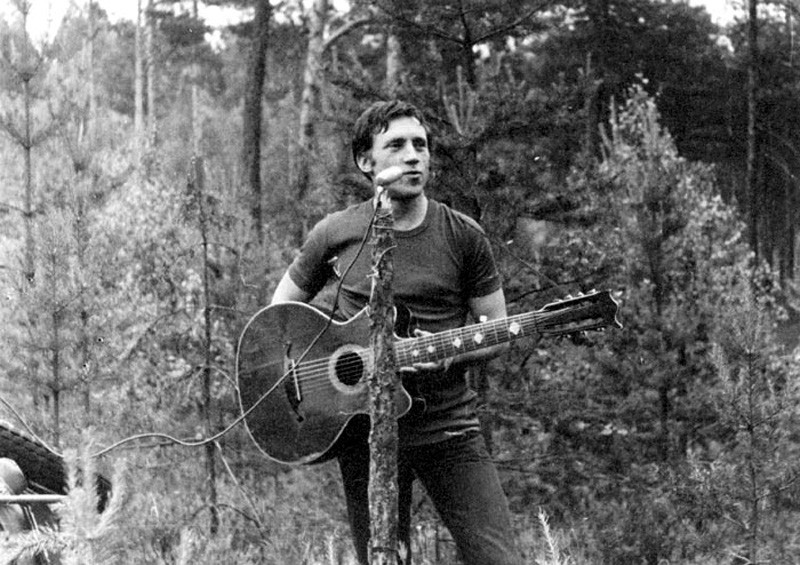

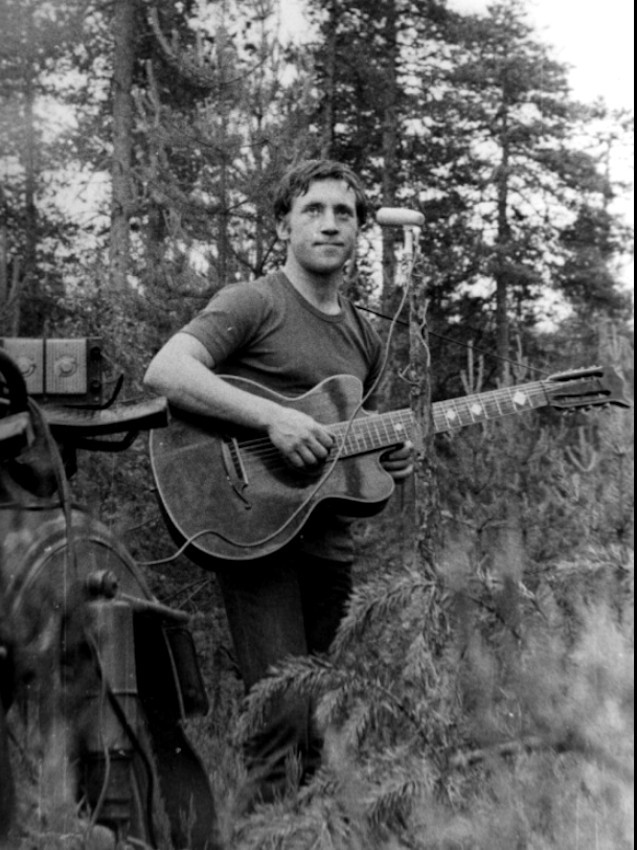

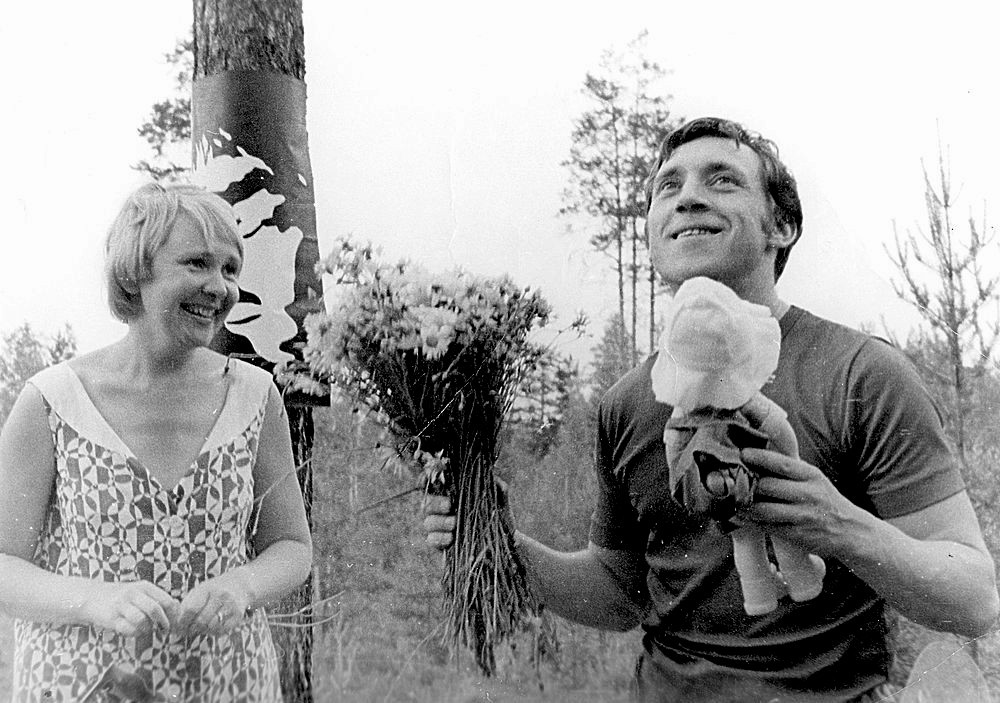

Vysotsky performed everywhere—on student hall stages, in polytechnic institutes, in cramped apartments, at massive impromptu gatherings, and even in the rain, hail, and snow. He was an artist who lived for his audience, no matter the setting or the weather. One such example took place on July 1, 1972, when the Leningrad club of bard music Vostok organized an informal outdoor concert by Vladimir Vysotsky near the forest lake Lampushka on the Karelian Isthmus in the Leningrad region.

There was no advertising for the event—news of it spread purely by word of mouth, as friends told friends and acquaintances passed the message along. Despite this, people came, drawn by the chance to hear Vysotsky perform live. Alongside him, other bards like Galina Astafyeva, Mikhail Kane, and Yuri Kukin sang for the audience.

During Vysotsky’s set, the skies opened up, and rain began to pour. But he didn’t stop. Instead, he stepped out into the rain, guitar in hand, and played as though the weather was part of the performance. Drenched but unfazed, Vysotsky sang for his people with the same intensity as if it were a grand stage.

Moments like this showed how deeply Vysotsky loved his audience. He didn’t just perform for them—he connected with them, sharing in the same rain and mud, the same raw and unpredictable reality of life. This performance, under gray skies by a quiet forest lake, remains one of many vivid examples of his dedication to his fans and his unshakable bond with the people.

Yet his fame came with challenges. Soviet authorities were wary of his defiant nature and limited his exposure on state-controlled media. His struggles with addiction didn’t help matters. His personal life was just as stormy—his first marriage ended quickly, his second brought him two sons, and his third, to Marina Vlady, was filled with both love and turbulence.

On July 3, 1980, one of Vladimir Vysotsky’s final performances took place at the Lyubertsy City Palace of Culture. Despite feeling unwell, the artist played a grueling two-hour concert, far exceeding the planned 90 minutes. On July 18, he made his last appearance on the stage of the Taganka Theatre in one of his most iconic roles—Hamlet. Witnesses recall that during this performance, Vysotsky barely managed to finish the play, visibly struggling with his deteriorating health.

Just days later, on July 23, Vysotsky’s condition took a severe turn for the worse. “Volodya’s state was terrible. It became clear that we either had to take more decisive actions and try everything to save him or abandon all efforts entirely. Any intervention was dangerous, but there was no other option. We decided that we had to act. However, his friends said it was too great a responsibility and insisted on getting his parents’ consent first. We agreed to hospitalize Volodya on July 25. He was in critical condition, but it didn’t feel like he was dying,” said Dr. Leonid Sulpovar from the Sklifosovsky Institute for Emergency Medicine, as quoted by Novye Izvestiya.

July 24 became the last day of Vysotsky’s life. Accounts describe him wandering around the apartment, groaning in agony, unable to find peace, and barely conscious. At one point, he approached his close associate, Semen Yanklovich, and said, “You know, I’m going to die today.” Yanklovich later called Fedotov, a doctor in Vysotsky’s inner circle, asking him to intervene. However, what followed has cast a long shadow over the final hours of the great bard’s life.

Both Fedotov and the friends he surrounded himself with have come under public scrutiny for their handling—or mishandling—of the situation. There have been allegations that those closest to Vysotsky failed to provide him with adequate medical attention when he needed it most. Even members of his immediate family were reportedly kept away, including his young son, who was allegedly turned away in an unceremonious and cruel manner when he tried to visit his father on the day of his death.

Some have theorized that the reluctance to bring Vysotsky to the hospital was tied to fears among those around him about their own potential complicity in his drug use. Whether or not his condition would have been treatable if he had received prompt medical care remains a haunting, unanswered question.

Later, Fedotov recounted: “I had just finished a shift—tired and drained. I lay down and fell asleep, probably around 3 a.m. I woke up to an eerie silence, as if something had jolted me awake. I rushed to Volodya. His pupils were dilated, unresponsive to light. I tried to breathe for him, but his lips were already cold. It was too late. Between 3:00 and 4:30 a.m., his heart stopped due to a heart attack.”

In one of his final poems, Vysotsky wrote:

“I’m less than fifty—forty-something,

I’m alive, kept by you and God for twelve years.

I have something to sing before the Almighty,

I have something to justify myself with.”

Vladimir Vysotsky passed away during the height of the 1980 Moscow Olympics, an event the Soviet authorities were determined to shield from anything that could overshadow its global grandeur. As such, his death was deliberately minimized in official media. The passing of one of the greatest poets, actors, and bards of the Soviet era was marked only by two brief obituaries—one in Vechernyaya Moskva and another in Sovetskaya Rossiya. At the Taganka Theatre, where Vysotsky had become a legend, a modest announcement was placed above the ticket window: “Actor Vladimir Vysotsky has died.”

Not a single person returned their tickets; instead, they kept them as cherished relics.

However, news of his death spread quickly, despite the authorities’ attempts to suppress it. A massive crowd gathered outside the Taganka Theatre, refusing to leave for days. On the day of his funeral, thousands of mourners filled the streets, with some even climbing onto nearby rooftops to get a glimpse of the ceremony. It’s estimated that around 40,000 people came to say goodbye to the artist who had touched their lives in profound and unforgettable ways.

Vladimir Vysotsky passed away on July 25, 1980, during the Summer Olympic Games being held in Moscow. On July 28, 1980, Vladimir Semyonovich was laid to rest at Vagankovo Cemetery.

Today, Vysotsky’s legacy is everywhere—streets and buildings bear his name, festivals celebrate his work, and his music lives on. For Russian-speaking people, he’s more than an artist; he’s a cultural icon.

© Sputnik / Ilya Pitalev

And yet, every January 25, I can’t help but wonder: what if he’d lived longer? I think he would’ve adapted, like so many Soviet stars did in the 1990s and 2000s. Maybe his career would’ve followed a trajectory like Alexander Rozenbaum’s, but perhaps even bigger—Vysotsky was a trained actor, after all. We might’ve seen decades of new work from him, in theater, film, and music. But that wasn’t his fate. Instead, he’s frozen in time, a fateful poet who left us too soon, at the peak of his popularity.

Today, millions of Russian speakers will remember him by the millions of Youtube videos of his performances that have ranked up millions of view on their own, or by reading his poetry and short stories, or by playing his songs with his friends, or by just whistling a song and raising a shot of vodka in his honor.

Happy Birthday Volodya, we miss you everyday.

Sources:

Лесной концерт, 1 июля 1972 года

Похороны Высоцкого. Уникальные снимки прощания с легендарным артистом