The Soviet Underground

This article was originally written for Literary Kicks in 2002. I have made some major edits in 2025.

In the waning years of Stalin’s reign, a profound cultural awakening began to stir within the Soviet Union: the Bard or Guitar-Poetry movement. Emerging in the late 1950s and flourishing in the 1960s, this movement irrevocably transformed Russian poetry, music, and cultural identity. At its heart were poets wielding guitars, their melodies laced with longing, defiance, and hope. Among these, Bulat Okudzhava stood as a foundational figure—a voice resonating with a generation yearning for authenticity.

Yevgeny Yevtushenko, himself a towering figure in Russian poetry, once described Okudzhava’s ascent: “Popularity came to him when he picked up his guitar and started singing a very simple and very melodic music to his poems.” Okudzhava’s songs, deceptively straightforward yet rich in emotional depth, became anthems of a quiet resistance. Students and workers across the USSR gathered in secret to listen to his music, shared through countless illegal tapes. His poignant verses and stirring melodies transcended mere art—they were acts of rebellion against a regime that sought to suppress individuality.

The Roots of the Bard Movement

The origins of the Bard movement are deeply intertwined with the collective memory of war and survival. The aftermath of World War II left an indelible scar on the Soviet Union. Cities lay in ruins, families were shattered, and the specter of Stalin’s purges loomed over the population. A generation grew up amid this devastation, their lives shaped by hunger, displacement, and the ever-present specter of annihilation. Yet, it was within this harsh reality that a vibrant cultural resistance began to take shape.

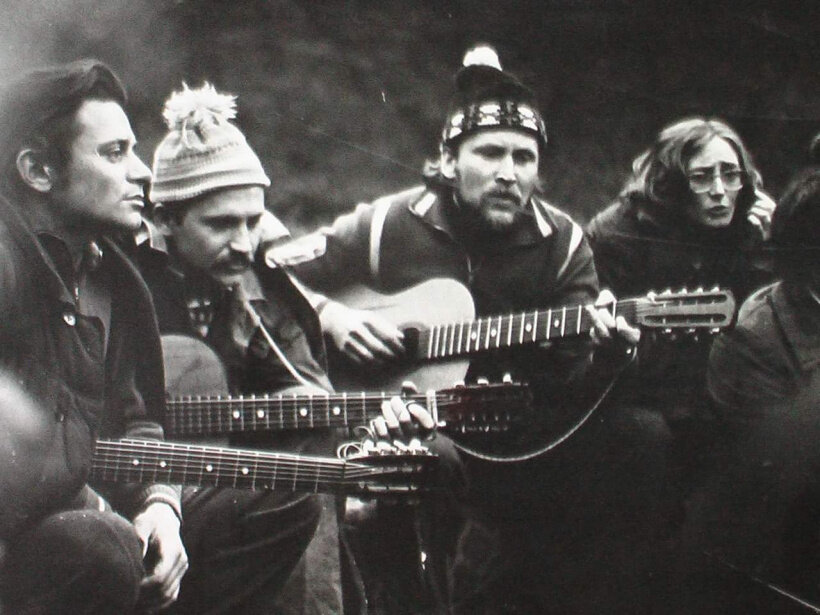

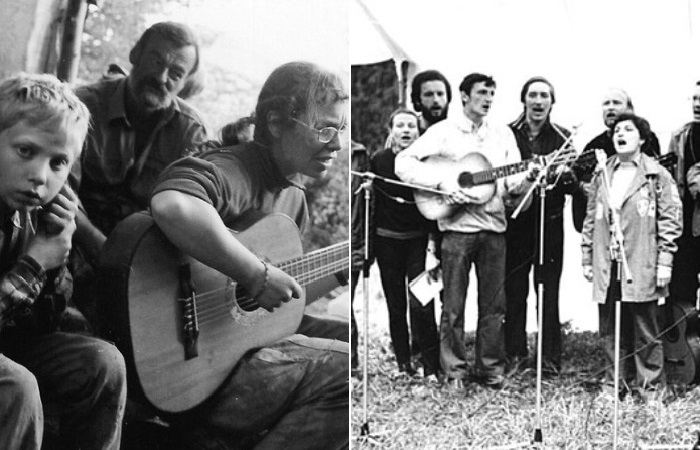

The 1950s were a paradoxical time in Soviet history. The nation was rebuilding from the war, but its people lived under a regime that demanded conformity and silence. In this stifling atmosphere, young intellectuals turned to music and poetry as a means of expression and escape. They gathered in cafés to debate philosophy, climbed mountains to find solace in nature, and poured their experiences into verses set to the strumming of guitars. Their songs were both deeply personal and universally resonant, capturing the complexities of a generation.

This movement had predecessors in the urban romances and musical miniatures of Alexander Vertinsky, whose melancholic songs in the early 20th century laid a foundation for the emotive style of the bards. Yet, the Bard movement’s true genesis lies in the years following the Great Patriotic War. It was born of the stark realities faced by a generation that had witnessed incomprehensible loss and sought solace in creativity.

The Era of the Sixties: A Golden Age

The 1960s, often regarded as the “golden age” of the Soviet Union, provided fertile ground for the Bard movement. The period of Khrushchev’s “Thaw” brought a temporary loosening of censorship and ideological control, encouraging artistic experimentation and intellectual exploration. On February 25, 1956, Nikita Khrushchev delivered his historic speech denouncing Stalin’s cult of personality. This moment marked the beginning of societal democratization and the rise of liberal sentiments. Young intellectuals, inspired by newfound freedoms, began to engage with poetry, music, and art in unprecedented ways.

The cultural atmosphere of the Thaw fostered the emergence of the “singing poets,” individuals who wrote both verse and music, performing their compositions with minimal accompaniment. This movement prioritized lyrics over melody, aligning the bards with the literary rather than the musical tradition. Their songs resonated deeply with audiences, offering solace, inspiration, and a sense of shared experience in an era of cautious optimism.

However, the Thaw was short-lived. Following the Cuban Missile Crisis and Khrushchev’s removal from power in 1964, censorship tightened once more. By the 1970s, the Soviet Union had entered the stagnation of the Brezhnev era. Yet, the seeds sown during the Thaw continued to bear fruit, as the Bard movement evolved and adapted to the changing political landscape.

Songs of Defiance

The Bard movement was more than an artistic endeavor; it was a lifestyle, a philosophy, and an act of defiance. Through their songs, these bards challenged the rigid orthodoxy of Soviet culture. Their works were circulated as magnitizdat (illegally copied tapes), spreading like wildfire across the country. While officially sanctioned poets like Pasternak and Yevtushenko were celebrated on the international stage, it was the underground bards who truly captured the hearts of the Russian people. Their lyrics offered a counter-narrative, one that spoke to the struggles, hopes, and dreams of ordinary citizens.

Bulat Okudzhava’s life and work exemplify this ethos. Born in 1924 to Georgian and Armenian parents, Okudzhava experienced both privilege and persecution. His father, a high-ranking Party official, was executed during Stalin’s purges, and his mother was imprisoned in the Gulag. Orphaned and disillusioned, Okudzhava volunteered for the Red Army at just 17 years old, serving bravely during World War II. These formative experiences shaped his poetry, infusing it with themes of loss, resilience, and a yearning for freedom. Songs like The Blue Trolleybus and The Black Cat encapsulated the paradoxes of Soviet life: its melancholy, absurdity, and fleeting joys.

A Symphony of Voices

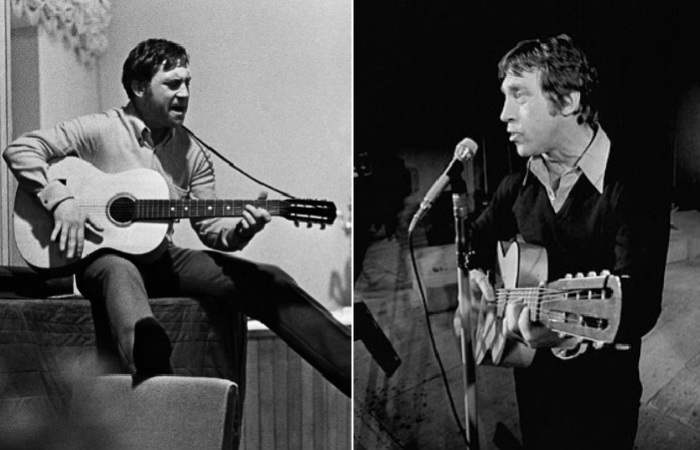

While Okudzhava laid the groundwork, the Bard movement was far from homogeneous. Each bard brought a unique voice to the collective symphony, reflecting the diversity of Soviet experiences. Vladimir Vysotsky, with his gravelly voice and searing lyrics, became a cultural icon whose fame transcended borders. His songs tackled themes of war, repression, and existential despair with a raw intensity that captivated audiences. Vysotsky’s performances were electrifying, his words cutting through the air like a blade, leaving listeners both devastated and inspired.

Vysotsky’s artistry extended beyond music. As a trained actor, he brought the same visceral intensity to his performances on stage and screen. His portrayal of Hamlet at the Taganka Theater became legendary, embodying the tormented soul of a nation grappling with lies, power, and oppression. His death in 1980 at the age of 42 marked the end of an era, yet his legacy remains a defining element of Russian cultural identity.

Alexander Galich, another prominent figure, used his biting wit to critique the absurdities and cruelties of Soviet bureaucracy. His songs were acts of intellectual resistance, earning him both adoration and exile. Forced to leave the Soviet Union, Galich continued to write and perform abroad, his work serving as a bridge between the silenced voices of his homeland and the free world.

In contrast, Yuri Vizbor’s lighthearted ballads celebrated nature and camaraderie, offering a respite from the harsh realities of daily life. His melodies, often inspired by the wilderness, reflected a deep longing for freedom and connection. Vizbor’s ability to capture the simplicity of shared human experiences made him beloved among both urbanites and rural communities.

The movement also saw the emergence of female voices like Veronika Dolina. Her introspective songs brought a fresh perspective to the male-dominated genre, exploring themes of love, loss, and the quiet struggles of existence. Dolina’s delicate yet resolute voice resonated deeply with her audience, solidifying her place among the greats.

The Female Voices of the Bard Movement

The Bard movement, often seen as male-dominated, also included remarkable contributions from women whose work brought diversity and depth to the genre. A prominent figure was Ada Yakusheva, known for her poignant songs such as You Are My Breath and I Walk Along a Long Road. As the wife of Yuri Vizbor, Yakusheva influenced his creative journey while establishing her own legacy as a bard. Her music combined lyrical simplicity with emotional resonance, earning her a lasting place in the pantheon of Russian bards.

Another influential bard, Veronika Dolina, began her career in the 1970s, composing introspective songs that explored themes of love, loss, and identity. Her delicate yet powerful voice defied initial skepticism, eventually earning widespread acclaim. Dolina’s albums, such as Elitarnye Shtuchki (Elite Pieces), achieved remarkable success, and her poetic contributions expanded the narrative scope of bardic music.

Galina Khomchik and Zoya Yaschenko further enriched the tradition. Khomchik gained recognition through the Songs of Our Century project, while Yaschenko’s group, White Guard, blended bardic sensibilities with rock influences. These women’s contributions challenged traditional perceptions, proving that bardic music was not confined to a singular perspective or gender.

Grushinsky Festival and the Legacy of the Bards

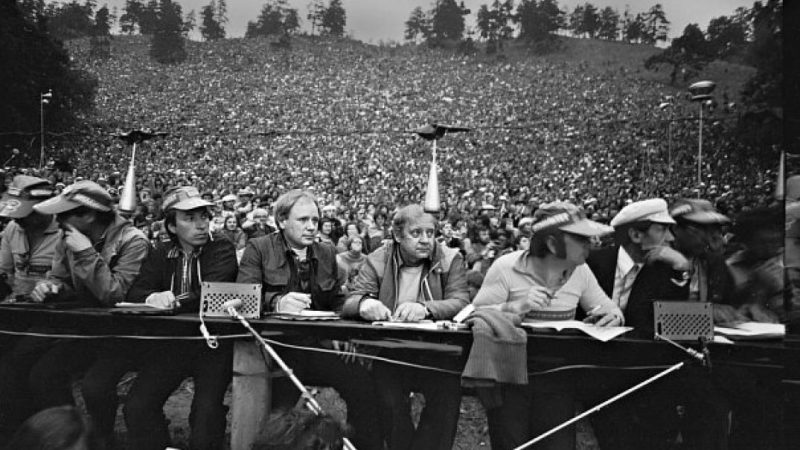

A significant milestone in the Bard movement was the establishment of the Grushinsky Festival in 1968, named in honor of Valery Grushin. Held annually near Samara, this festival became a gathering place for bards, enthusiasts, and newcomers to the genre. Its iconic floating stage, shaped like a guitar, symbolized the movement’s enduring spirit. The festival provided a platform for artistic expression, fostering a sense of community and inspiring future generations to embrace the bardic tradition.

Even as the Bard movement’s prominence waned in the late 20th century, its influence persisted. Modern bards continue to draw inspiration from their predecessors, blending traditional forms with innovative techniques. While their songs may no longer dominate public consciousness, they remain cherished as embodiments of resilience, creativity, and the enduring power of art.

Translating the Spirit of a Movement

Translating Russian bard poetry is a formidable task. The challenge lies not only in capturing the literal meaning of the words but in conveying the rhythm, emotion, and cultural nuances that define the genre. In my translations, I have sought to preserve the essence of the original—to offer readers a glimpse into the soul of a movement that spoke for millions. As Okudzhava wrote:

Song as short as life itself,Somewhere heard on the road.She has piercing words,And a melody that’s almost enlightening.

These songs, born from hardship and hope, endure as luminous beacons of the human spirit, illuminating the path of resilience and creativity in the face of oppression.

Enduring Legacy

The Bard movement was not merely an artistic phenomenon but a cultural revolution. It gave voice to the silenced and courage to the oppressed. By the late 20th century, songs like Vadim Egorov’s Rains and Alexander Gorodnitsky’s Leather Jackets had entered the canon of Russian popular culture. Their authorship became secondary as these songs were absorbed into the collective memory, testaments to the enduring power of art to preserve history.

The cultural impact of these artists also extends into modern Russian identity. Their songs, once whispered in defiance, are now sung openly as symbols of resilience and creativity. In the face of oppression, the bards proved that even the simplest melody could carry the weight of a nation’s longing for truth and freedom.

The Global Connection

Beyond the Soviet Union, the Bard movement found parallels in the singer-songwriter traditions of other countries. Figures like Bob Dylan in the United States, Georges Brassens in France, and Fabrizio De André in Italy shared the bards’ commitment to using music as a vehicle for social critique and personal expression. In many ways, the Bard movement was part of a larger global awakening, where individuals wielded guitars as instruments of change and defiance.

In this interconnected world of melody and verse, the legacy of the bards continues to inspire. Their voices, forged in the crucible of adversity, remind us of the enduring power of art to illuminate the human experience and challenge the status quo.