The Last Drink: Writers & Alcohol

This article was originally written in 2018.

There’s a certain familiarity in the way writers are drawn to alcohol—an orbit of longing, self-doubt, and solace. As someone who reads obsessively and writes, I’ve noticed the same story unfold time and again, not just on the page but in the lives of those who create. It’s as though a secret thread connects so many of them—genius intertwined with self-destruction, the bottle passed from one hand to the next. I’ve wondered if it’s the heightened sensitivity of writers that makes them more susceptible to their demons, or if it’s the act of writing itself—bearing witness to the beauty and brutality of life—that drives them to drink.

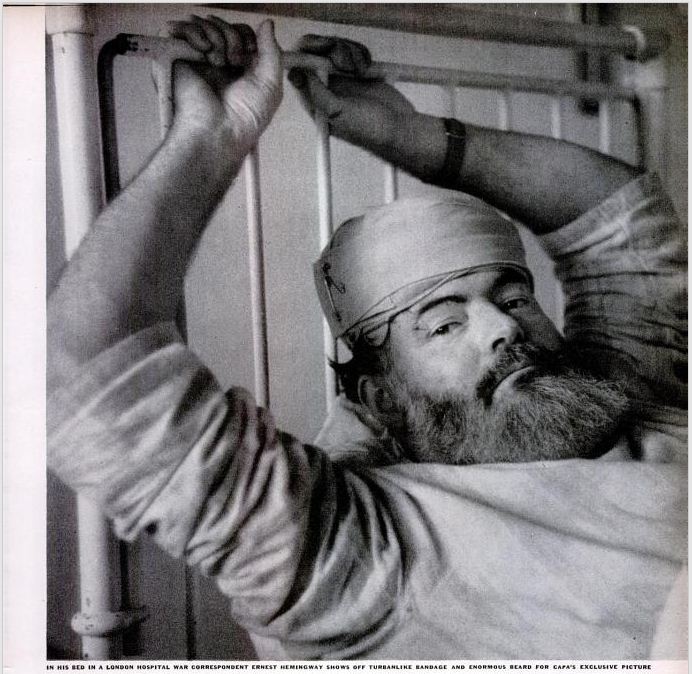

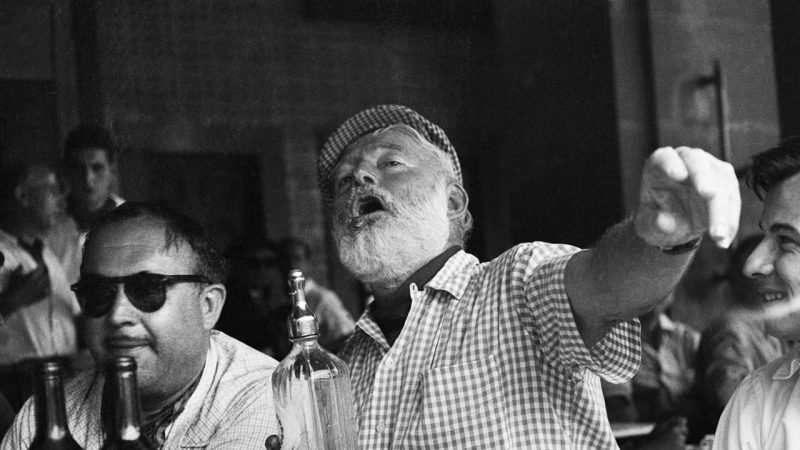

Ernest Hemingway looms large in this narrative, a man who seemed carved from the same stone as his rugged prose. He has been mythologized almost beyond recognition—his daiquiris in Havana, his whiskey-soaked nights in Paris. But beneath the stories of bravado was a man buckling under the weight of expectation, haunted by wounds both visible and invisible.

Hemingway’s relationship with alcohol was destructive, driven less by camaraderie or connoisseurship and more by a relentless impulse toward self-destruction. Anthony Burgess, in his biography, recounted that Hemingway could drink three bottles of Valpolicella before noon, followed by a string of daiquiris, Scotch, tequila, and martinis without vermouth. The punishment his body endured was immense—liver damage, kidney issues from icy Spanish waters, and injuries from careless accidents.

Despite a 1937 diagnosis of liver damage, Hemingway refused to stop drinking. By 1957, his friend and doctor A.J. Monnier wrote a heartfelt plea: “My dear Ernie, you must stop drinking alcohol. This is definitely of the utmost importance.” But Hemingway couldn’t stop. As journalist John Walsh noted, the accumulation of physical and mental wounds from years of addiction left him with few ways to fight his despair.¹

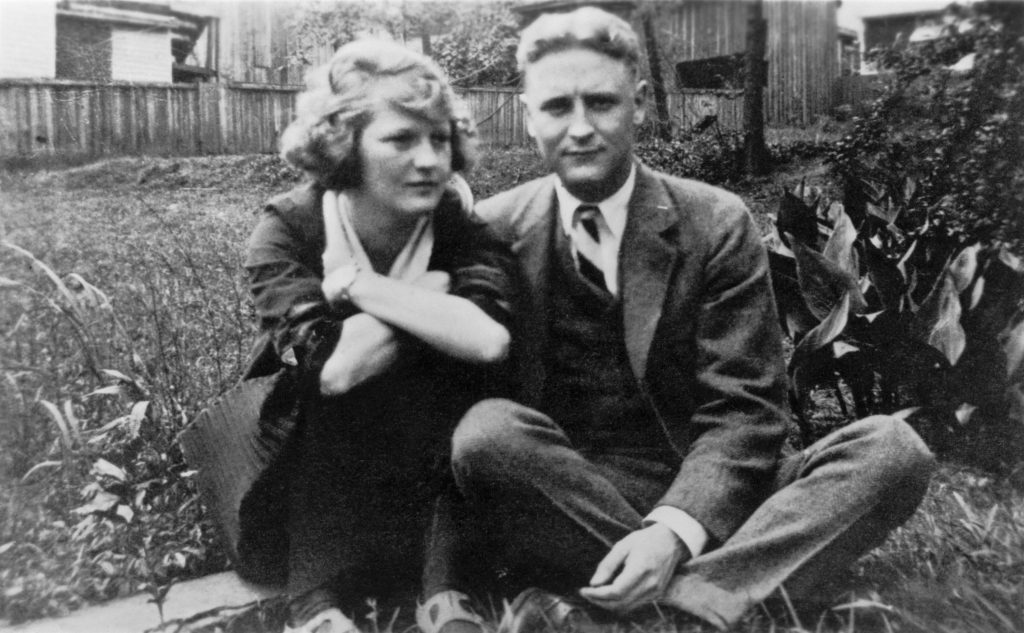

F. Scott Fitzgerald is another familiar ghost in the room. I’ve read The Great Gatsby more times than I can count, entranced by the shimmering dreamscape he conjured. But Fitzgerald’s life was anything but golden. “First you take a drink, then the drink takes a drink, then the drink takes you,” he wrote, as though he could see his future unfolding in a glass. What we often overlook, though, is that Fitzgerald did try to wrest himself from the grip of alcohol.

By the final year of his life, Fitzgerald had committed to sobriety, as his partner Sheilah Graham recalled in Beloved Infidel. She described that year as one of the happiest times they had together—a period when Fitzgerald seemed more determined to make peace with his demons.

On December 20, 1940, they attended the premiere of This Thing Called Love. Leaving the theater, Fitzgerald stumbled, dizzy, but reassured Graham that it wasn’t drunkenness, saying, “I suppose people will think I’m drunk.” The next day, as he read his Princeton Alumni Weekly, he stood suddenly, gripping the mantelpiece before collapsing to the floor. Graham’s attempts to revive him failed. When the building manager, Harry Culver, arrived, he knew immediately: Fitzgerald was gone. At 44, he succumbed to a heart attack, his final reckoning coming during a rare time of sobriety and clarity.²

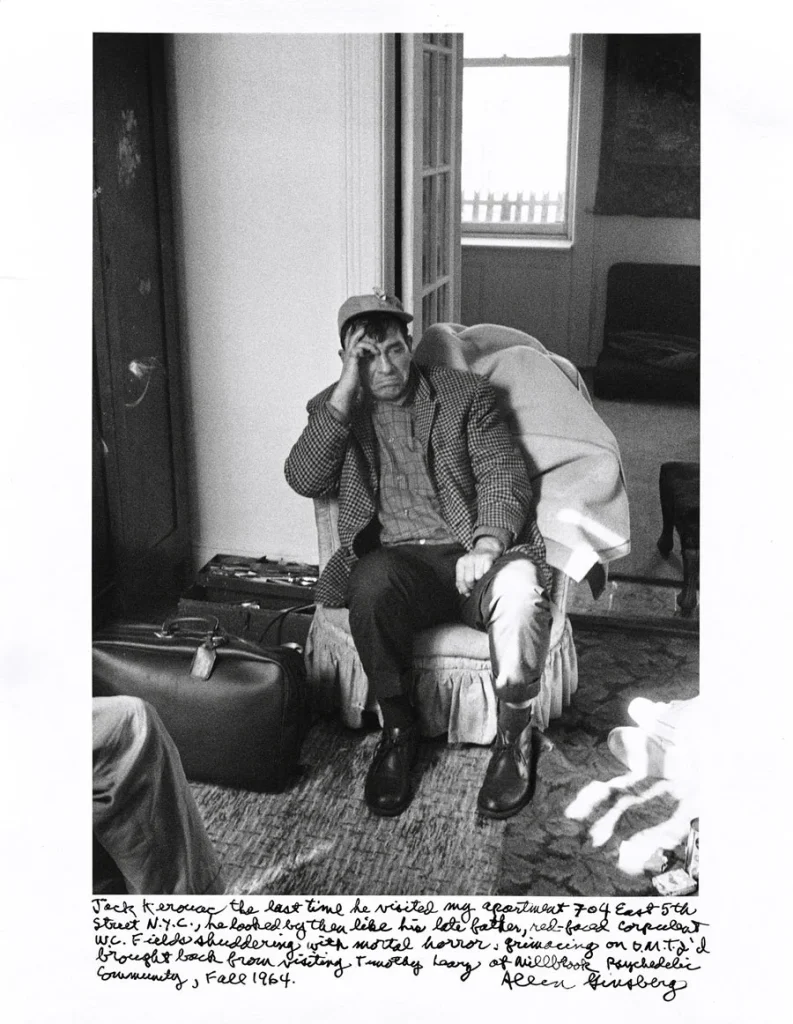

Jack Kerouac didn’t seem to fight as much as he surrendered. His novel On the Road gave voice to a restless generation, but his life veered into a slow collapse. I’ve always felt that Kerouac was burdened by the myth that sprang up around him—a free spirit when, in truth, he was often trapped by despair. I remember reading an interview where he said, “I am not a beatnik. I am not a bohemian. I am Catholic.” That raw honesty felt worlds apart from the larger-than-life persona the world projected onto him.

On October 21, 1969, Allen Ginsberg received a call from journalist Al Aronowitz: Jack Kerouac had died earlier that day in a Florida hospital. It was the second devastating call Ginsberg had received in just over a year and a half—the first had informed him of the death of Neal Cassady, the inspiration for On the Road and one of Kerouac’s closest friends. Ginsberg was saddened but not surprised. By then, Kerouac’s heavy drinking had spiraled to such an extent that even his closest friends wondered if he had a death wish.

Kerouac’s isolation deepened during his final years. He remarried, moved to Florida, and lived a reclusive life with his wife and his ailing mother. Ginsberg, who had once cherished Kerouac’s friendship, had drifted away, finding it too painful to watch his old friend deteriorate. The Jack Kerouac that Ginsberg remembered—the man who once poured his soul into his words—was now often a belligerent and sorrowful shadow of his former self.³

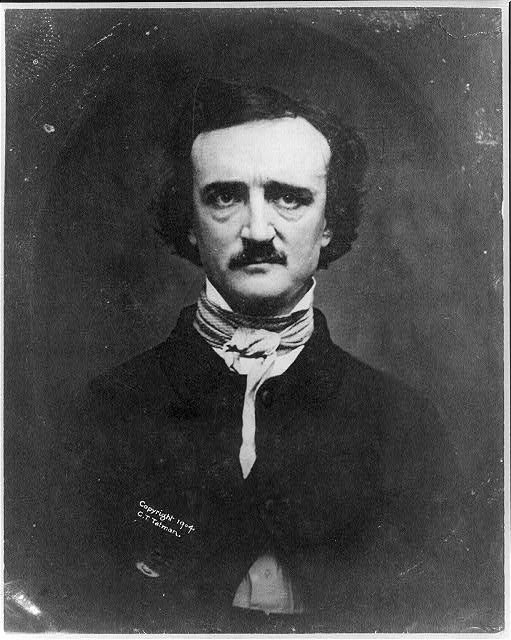

But the story stretches far back, well before the 20th century. Edgar Allan Poe haunts me—not just his stories, but the life behind them. Here was a man whose every success seemed chased by ruin. Found delirious in a Baltimore gutter and dead days later, Poe’s death remains a mystery. Some, like J.E. Snodgrass, the doctor who saw him, believed he succumbed to the effects of alcohol withdrawal, pointing to Poe’s history of drinking binges. However, Poe had recently joined a temperance society, and John Moran, the physician who attended him at the hospital, insisted that Poe hadn’t been drinking at all. The pattern of Poe’s illness—seeming to recover briefly before worsening—has led some modern researchers to suggest alternative causes, such as heart disease, epilepsy, or even late-stage rabies.⁴

He was only 40, yet his work pulses with the weight of centuries. There’s something unbearably poignant about the fact that the man who gave us The Raven and The Tell-Tale Heart couldn’t outrun his own heartbreak.

Even Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s unfinished masterpiece, Kubla Khan, feels like an echo of this struggle. Coleridge’s addiction to laudanum was well-documented, but it’s his self-reproach that sticks with me. He knew how addiction unraveled him, how it interrupted his mind’s grand symphony. And though his addiction was to opium rather than alcohol, it was still part of that same narrative—the creative mind caught in the jaws of something insidious.

Writers like Lord Byron and Thomas De Quincey indulged as part of their hedonism and intellectual experimentation, but the Romantic Era’s fascination with self-destruction makes me wonder if they romanticized it too much for their own good. And yet, even Byron’s legacy is clouded by tragedy—his insistence on excess as a way of life carried its own destruction.

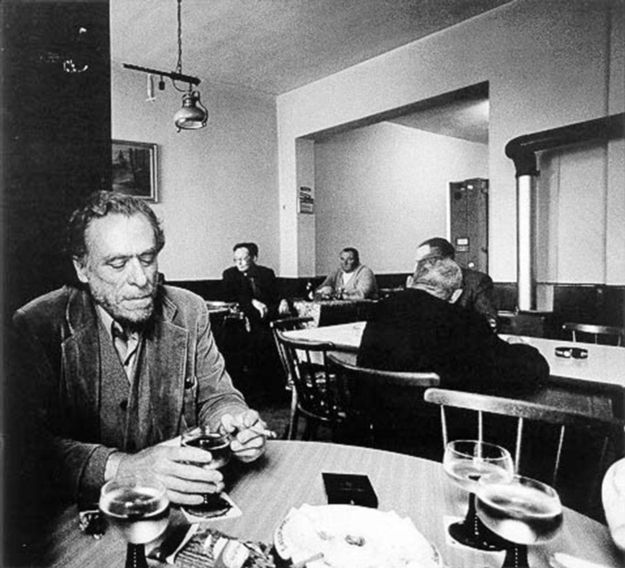

Charles Bukowski never romanticized his vices—he wielded them. His poetry and prose are stained with the rawness of his life: bar fights, unpaid rents, and half-empty bottles. I read Post Office when I was too young to understand its full weight, but even then, I felt the exhaustion of a man at war with the world and himself. Bukowski didn’t see drinking as a path to higher consciousness; for him, it was a coping mechanism, a way to navigate a world that didn’t care about people like him. Yet even in his cynicism, there was something almost tender—a strange resilience beneath the grime.

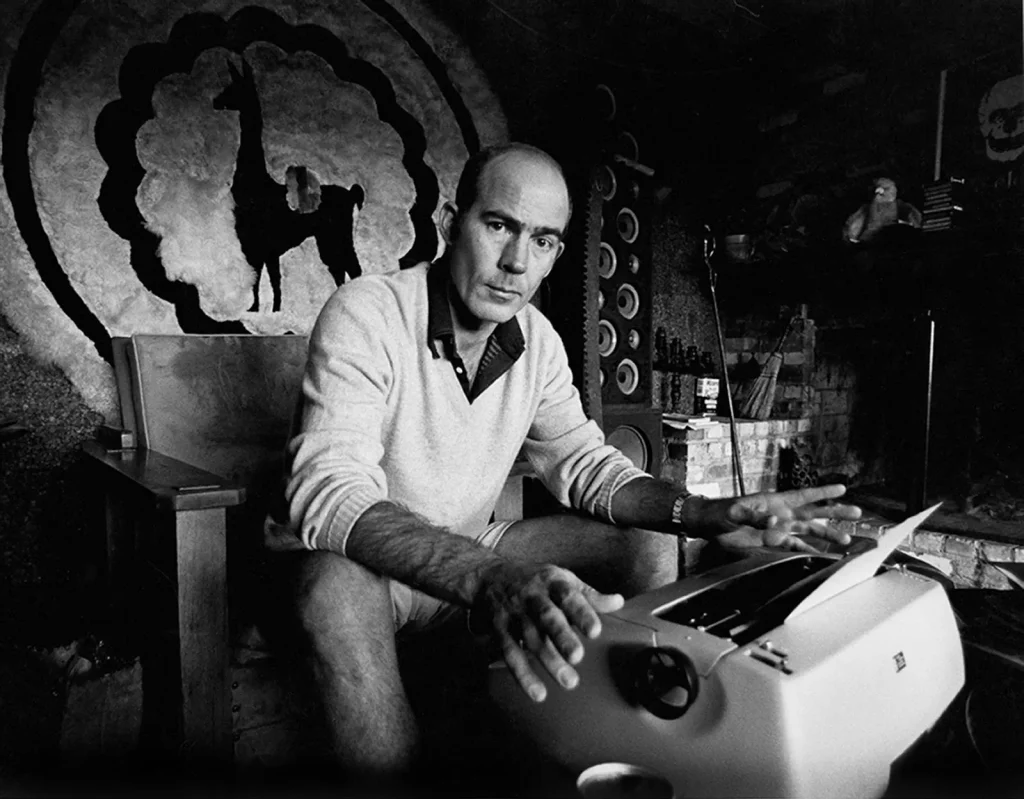

Then there’s Hunter S. Thompson, the wild-eyed prophet of gonzo journalism, who didn’t just drink but did everything to excess—booze, drugs, gunfire. Reading Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas feels like stepping into the mind of someone teetering on the edge of madness, and that’s exactly what Thompson wanted you to feel. But behind the antics and bravado was a man haunted by loneliness and a deep sense of alienation. In a 2016 interview with Huck Magazine, Thompson’s son, Juan, reflected that his father never drank to get conventionally drunk—there was no slurring or staggering—but rather, he drank because his body had grown dependent on alcohol, using it as a form of maintenance. Juan noted that this dependency, along with cocaine use, eventually eroded his ability to write. “The irony of it is that drugs and booze ended up undermining what was most important to him, which was writing,” Juan shared.⁵

As time passed, Thompson’s finances and priorities became tangled in addiction. According to Juan, there were moments when paying the mortgage took a back seat to paying the dealer. Despite this, writing always remained at the core of who Thompson was—his defining purpose. Yet, addiction took its toll, weakening his body and his ability to focus. Ultimately, it was the very thing that he believed fueled his creativity that contributed to his undoing.

I think about Dylan Thomas sometimes and his infamous last night in New York—18 whiskeys, or so the legend goes. But as David N. Thomas, the grandson of Dylan Thomas, notes in his book, the story may have been exaggerated. Ruthven Todd, a friend of Thomas, later checked with the bartender and found that it was more likely Dylan had six or at most eight drinks that night—though it made for a better tale to call it eighteen. Despite the embellishment, David N. Thomas emphasizes that Dylan was drinking heavily in his final year and that New York’s vibrant nightlife became an irresistible escape. His grandmother had warned that the American tours were taking too great a toll on him—physically and mentally.⁶

Living in New York myself during my 20s and 30s, I often stopped by the White Horse Tavern for one of their dark ales. It’s a humble place despite its history, and I’d sit there imagining the conversations and the quiet unraveling of great writers who once drank there. Thomas’s poetry is so luminous, so alive with rhythm and fire, that it’s hard to reconcile with the chaos of his death. “Do not go gentle into that good night,” he wrote, and yet he did, leaving behind words that begged for another fate.

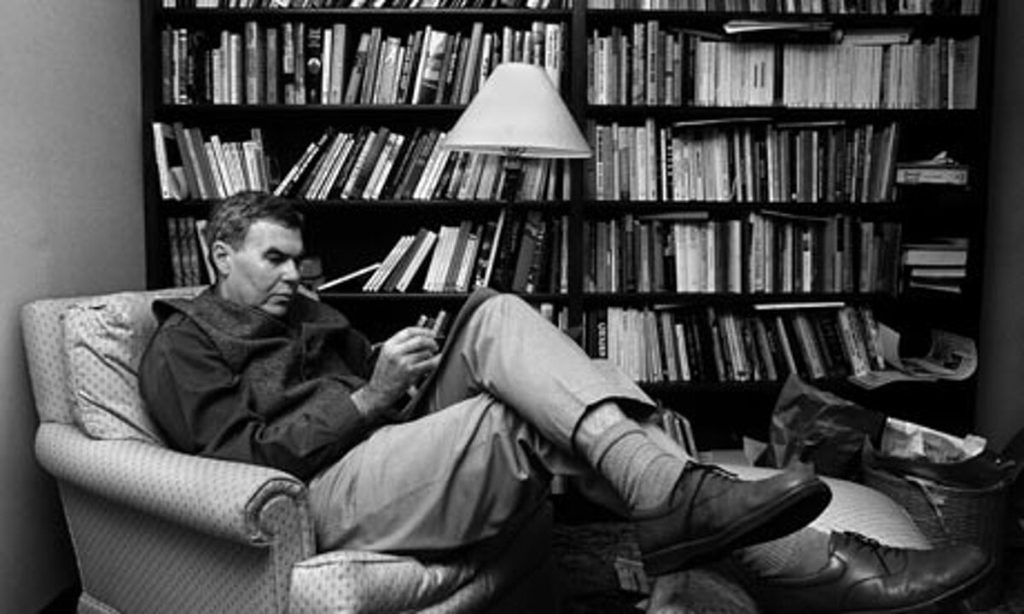

Raymond Carver’s life is one of those rare stories where sobriety didn’t just save the man—it sharpened his art. His partner Tess Gallagher reflected in an essay that she met Carver five months after he had quit drinking, and she only knew the sober Ray. She recalled how his decision to stay sober transformed his life and their shared creative world. Gallagher described how they celebrated his sobriety with simple joys, like sharing sparkling apple juice and giving meaningful gifts tied to his stories. Carver viewed the day he quit—June 2, 1977—as the most important day of his life. By the time he passed at age fifty from lung cancer, he had built a decade of clarity and connection through language. Visitors still leave messages at his grave, saying, “Ten years sober, Ray! Life is sweet—you bet!”

Gallagher believed Carver had traded a deadly intoxication for an intoxication with storytelling and life. It’s a reminder that recovery isn’t about erasing pain but finding a way to honor it without succumbing. Carver once wrote in Gravy, “I don’t have any complaints. Not a single one.” And that’s what survival feels like—not invincibility, but gratitude, fragile and precious. Jean Rhys, after decades of obscurity and alcoholism, returned to the literary world with Wide Sargasso Sea, a novel so brilliant it silenced her critics. But Rhys’s life was still marked by isolation, even triumph shadowed by loneliness.

There’s something seductive about the myth of the drunken genius. I get it—the idea that suffering sharpens creativity, that the artist must endure torment to produce beauty. But I’ve read enough, lived enough, to know that suffering doesn’t make art. It makes wreckage.

I often wonder if it’s a self-inflicted wound—if some writers feel they have to live up to the romantic vision of the haunted, troubled, alcoholic or drug-addicted artist. It seems as though some young writers believe that by indulging in that lifestyle, they gain a kind of mystic connection to their idols and, through it, attain inspiration. I noticed this streak during my time in New York, especially while studying at NYU and spending time with artists. There was often a Bukowski imitation that felt more like a performance than a reality.

But the truth is, alcoholism affects everyone—not just writers. It touches janitors, Sunday school teachers, therapists, doctors, and yes, writers. What matters is what you do about it. Stephen King is an example of someone who recovered and thrived, proving that sobriety can lead to a life just as creative and prolific. Augusten Burroughs, too, has shared his story of recovery. And there are many others who have chosen not to discuss it publicly but continue to write and create without the crutch of addiction. Writers like Leslie Jamison have dissected this myth, especially in her memoir The Recovering, which examines the cultural fixation on destruction as a creative crucible.

What remains, though, is that persistent negotiation between creation and destruction, between solace and annihilation. The last drink is never just a drink—it’s a reckoning.

When I think about Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Kerouac, Bukowski, and Thompson, I see brilliance, yes—but also fragility. Their works live on, but the cost was steep. Genius doesn’t make anyone immune to suffering. But maybe, by remembering their struggles, we can resist glorifying them. As Carver wrote: “It’s been gravy all the way.” And that’s what survival feels like—not invincibility, but gratitude, fragile and precious.

We hold on where they couldn’t, and in that act of holding on, we honor not just their genius, but their humanity.

References

- Timberg, Scott. “Hemingway Drank Too Much: Our Strange, Macho Romance with Papa’s Alcoholism.” Salon, July 21, 2016. https://www.salon.com/2016/07/21/hemingway_drank_too_much_our_strange_macho_romance_with_papas_alcoholism/.

- Graham, Sheilah, and Gerold Frank. 1958. Beloved Infidel the Education of a Woman. [1st ed.]. New York: Holt. http://books.google.com/books?id=QeIcAAAAIAAJ.

- Ginsberg, Allen. “The Day After Kerouac Died.” The New Yorker, October 20, 2019. https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/allen-ginsberg-the-day-after-jack-kerouac-died.

- “Edgar Allan Poe.” Encyclopedia Britannica. Accessed October 26, 2019. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Edgar-Allan-Poe.

- Wray, Daniel Dylan. “Busting Myths and Reminiscing with Hunter S. Thompson’s Son.” Huck, May 23, 2016. https://www.huckmag.com/article/busting-myths-hunter-s-thompsons-son.

- Thomas, David N. Fatal Neglect: Who Killed Dylan Thomas? Bridgend: Seren, 2008.

- Gallagher, Tess. “Instead of Dying.” The Sun, December 2006. https://www.thesunmagazine.org/articles/27886-instead-of-dying.

This was a fun read, and sad all the same. Addiction is a dark horse to ride. One thing I’d add is that many artists throughout time have talked about using drugs and alcohol to transport them and to seperate from social and learned stigmas and to act and create uninhibited. There seem to be many ways to get here, drugs and alcohol seem to be for the impatient.